Adolescence is a time of significant growth and development that ebbs and flows. Teens can have both a sense of invisibility and vulnerability. Their ability to consider the future, think abstractly, understand others' perspectives, and understand long term consequences is growing but not full y developed. Peer relationships are of utmost importance and yet are fraught with uncertainty. All of this is fueled by easy access to technology and sexual content. Although research indicates that youth want access to accurate information on relationships, sex education, consent, and the rules and laws that guide these decisions, few receive quality content. Further, addressing problematic sexual behavior in teenagers is more complex because the behavior may also be illegal, depending on the laws in the jurisdiction. Background information about adolescents' sexual behavior can be found here.

y developed. Peer relationships are of utmost importance and yet are fraught with uncertainty. All of this is fueled by easy access to technology and sexual content. Although research indicates that youth want access to accurate information on relationships, sex education, consent, and the rules and laws that guide these decisions, few receive quality content. Further, addressing problematic sexual behavior in teenagers is more complex because the behavior may also be illegal, depending on the laws in the jurisdiction. Background information about adolescents' sexual behavior can be found here.

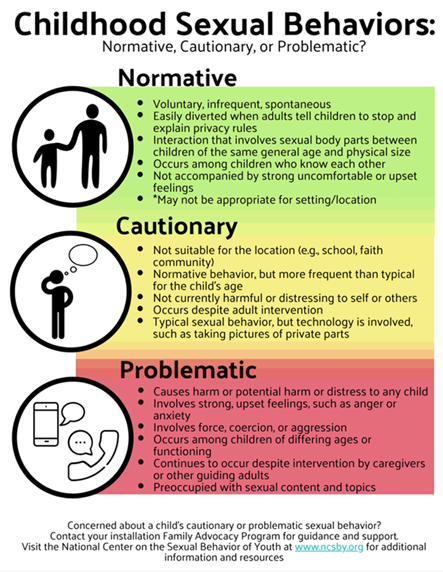

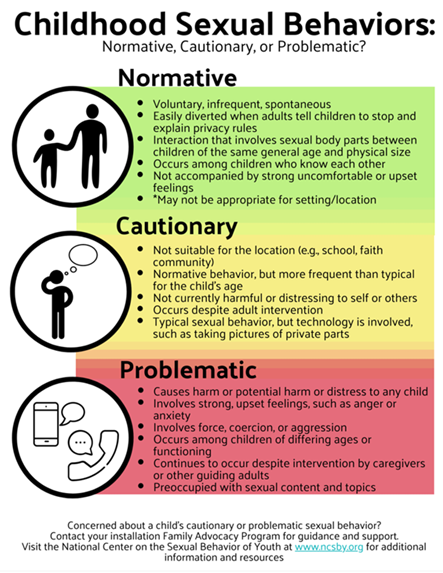

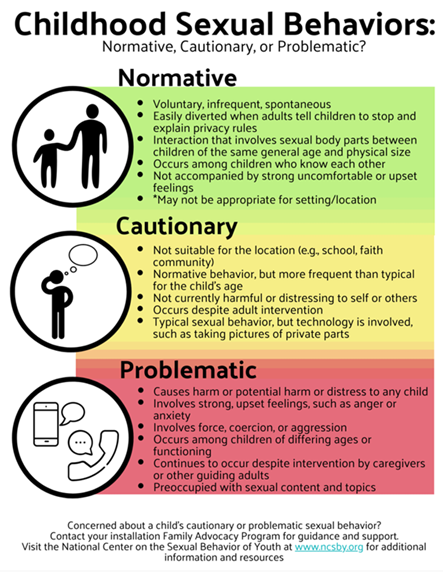

Normative sexual development information can be found here.

What are best practices in identifying and responding to problematic sexual behavior of youth?

Research indicates that teens with problematic or illegal sexual behaviors have three or more service systems involved in the response. Siloed systems can increase stress and hinder family engagement and progress. Best practices implement a strong, collaborative approach with:

- Child Protective Services

- Child Advocacy Centers

- Law Enforcement

- Juvenile Justice Agencies (probation, Juvenile / Family Court, Prosecution)

- Mental Health Providers

- Medical Providers

- Schools

- Service agencies that work with youth

What if the assessment indicates the teen does not have problematic sexual behavior?

- Concerns raised about the teen's sexual behavior may indicate a need for sex education or other supports for healthy relationship building skills. Brief education may be useful for the family.

- The assessment can provide guidance on next steps. It might reveal other difficulties, including other problematic behaviors, untreated mental health disorders, or significant family conflict.

What are some considerations for understanding teen behaviors and treatment?

Understanding how problematic sexual behaviors fit within the context of other behaviors, mental health difficulties, environment, and other risk and protective factors will influence treatment and case planning decisions.

Here are some considerations:

- What is the context of the sexual behavior? What individual, family, and situational factors impact the onset and maintenance of their problematic sexual behaviors?

- Do they demonstrate problematic sexual behaviors as part of a larger pattern of conduct problems and delinquent behaviors?

- Do they have a complex trauma history impacting their sexual development and behavior?

- Do they have atypical sexual interests, antisocial attitudes, and delinquent behaviors?

What situational or transitory factors are related to problematic sexual behaviors?

For many teens, problematic sexual behaviors are related to situational factors, such as:

- A normal surge of onset sexual interest and impulses.

- Lack of knowledge or misunderstandings about society’s rules regarding sexual behavior and not appreciating the wrongfulness of sexual misconduct.

- Insufficient adult monitoring.

- Inadequate sex education and support to build healthy relationship skills.

- Substance use.

- Exposure to sexual behavior through media or on the internet.

- Obstacles to age-appropriate peer relationships and social isolation.

- Negative peer influences.

Teens with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in the absence of other delinquent behaviors, may also fall into this category.

Some teens may have other difficulties like learning disabilities, intellectual disabilities, or developmental disabilities, such as autism, or fetal alcohol syndrome. They may have difficulties with impulse control and decision making. They may impulsively touch others’ private parts or violate physical boundaries.

Teens who have these difficulties sometimes respond to normal sexual feelings inappropriately. They may not have learned the rules or laws. They may struggle with reading or understanding others’ feelings. They may act in ways that are sexually inappropriate or even illegal.

Most youth with ADHD, developmental disabilities, or other mental health challenges or disorders do not engage in problematic sexual behaviors.

Treatment and case planning must consider the teen’s abilities, support, and learning style.

Disruptive Behavior Disorder or Delinquency

What if the problematic sexual behavior is part of a larger disruptive behavior disorder or delinquency pattern?

- Some teens engage in disruptive or aggressive behaviors that include violating laws or the rights of others. PSB may be part of a larger repertoire of concerning activities. Youth who engage in antisocial and delinquent acts often meet the criteria for Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD), Conduct Disorder (CD), Disruptive Behavior Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (NOS), or Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD).

- Common behavior patterns for youth with ODD or CD include outbursts or aggression in response to limit-setting, as well as provocative behaviors intended to annoy or harass others. Their behavior might follow similar triggers, such as rejection. This behavior could take the form of harassment.

- Sometimes, illegal sexual behaviors may relate to antisocial attitudes that justify these behaviors. Maybe they feel entitled to sex and are willing to use force.

- Others might commit statutory offenses that don’t always involve force, aggression, or even physical contact.

- And others may demonstrate severely nonsexual aggressive and dangerous conduct that has been ongoing from an early age, with intermittent sexual offenses.

Most youths with delinquent behaviors do not exhibit problematic sexual behavior. A multisystemic intervention, such as Multisystemic Therapy for Problematic Sexual Behavior (MST-PSB), is an evidence-based approach that could help.

Trauma and Adjustment Disorders

Are problematic sexual behaviors related to traumatic experiences? They may be directly or indirectly related to traumatic experiences. A common belief is that a child with problematic sexual behaviors has been sexually abused. While that is true for some teens, it is not universal. In fact, experiences of exposure to violence (physical abuse, domestic violence, bullying and community violence) has been more common. Youth with complex trauma histories often have more complicated clinical presentations requiring integrated treatment plans to address their multiple needs.

For more information about children’s response to trauma, visit the National Child Traumatic Stress Network (nctsn.org)

Atypical Sexual Interests and Serious Delinquency

Do problematic sexual behaviors reflect atypical sexual interests?

- In rare cases, the behaviors may reflect atypical sexual interests involving much younger, prepubescent children or coercive sexual activities.

- Sometimes, these atypical interests may resemble sexual traumas experienced by the youth – perhaps reinforced by multiple incidents or masturbatory activity – and physiological arousal responses involving pleasurable sensations or orgasms in pubertal youth.

- Because sexual interests and patterns of sexual arousal are still developing in teens, a diagnosis of Pedophilia is rarely and only used if the teen if 16 or older, and clearly meets the diagnostic criteria - as noted in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association - (DSM-V).

What if teens have problematic sexual behavior with atypical sexual interests?

- A small number of teens may display preoccupation, excessive sexual behavior, and/or atypical sexual interests. For them, sexual behaviors are the focus of treatment.

- They have difficulty managing their sexual arousal appropriately. They may demonstrate problematic sexual behavior across various contexts, such as at their school or home.

- Assessment and interventions must explore the antecedents, behaviors, and consequences of the behavior as well as triggers and causes.

- They might have inaccurate and distorted beliefs about sexual behaviors. They might not even recognize the behavior is inappropriate.

- Occasionally, these teens experience persistent arousal associated with inappropriate sexual interests, such as sexual arousal involving significantly younger children, themes of violence, or coercion.

- The Help Wanted program provides important guidance on preventing and responding to atypical sexual interests towards children (https://www.helpwantedprevention.org/). As does Talking for Change - https://talkingforchange.ca/

- WhatsOK is a website (whatsok.org) and a helpline (whatsok.org/ask) that offers free, confidential support and resources to youth and young adults (ages 14-21) with concerns about their own or a friend’s sexual thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.

What if the problematic sexual behavior is both atypical and delinquent?

In rarer cases, teens may demonstrate significant, early-onset, delinquent, and aggressive behaviors and sexual preoccupation or deviant sexual interests. These teens often present multiple, pressing treatment needs – often including co-occurring mental health challenges and disorders.

- Interventions should be prioritized to maximize the safety of all involved and reduce immediate risk factors. Interventions may initially require short-term residential placement and intensive services.

- After a comprehensive assessment, interventions need to target erroneous attitudes and beliefs related to problematic sexual behaviors.

- Interventions that facilitate impulse management and other identified risk factors are needed.

- Behavior management and collaborative, multisystemic safety plans involving parental and other adult supervision are needed to facilitate safety upon re-entry to the community.

Other Diagnostic Considerations

Assessment sometimes reveals learning difficulties and mental health problems – or a significant history of trauma or maltreatment. How these factors interact with PSB will determine risk factors and treatment needs.

What are some diagnostic considerations for youth with learning problems?

- Teens with problematic sexual behavior may have learning disorders or developmental difficulties. Some teens may have developmental delays, intellectual disabilities, or pervasive developmental disorders that impact not only learning but functioning across multiple domains.

- Providers should tailor interventions to match a teen’s learning style and capabilities.

- Teens with memory difficulties will likely need opportunities to have multi-modal learning material and have frequent repetition and practice.

- Many teens could benefit from additional support and structure in their home environment, including cues from their caregivers to use their new skills.

What are some diagnostic considerations related to problematic sexual behavior?

- “Problematic sexual behavior” is not a diagnosable condition, but it is clinically concerning.

- At times, problematic sexual behaviors represent an isolated or temporary problem.

- Sexual behaviors may be part of a pattern of delinquent activities or one of several disruptive behavior disorder symptoms.

- They might involve breaking the rules and violating physical boundaries. They may be consistent with other symptoms of disruptive behavior disorders, such as Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, Oppositional Defiant Disorder, Conduct Disorder, or Disruptive Behavior Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (NOS).

For more information about youth responses to traumatic life experiences, visit the National Child Traumatic Stress Network.

Treatment Planning and Interventions

What are some considerations for effective treatment planning and interventions?

Effective treatment plans will follow assessment. Ensure safety. Identify risks, intervention needs, and required responses.

Ongoing and timely reassessments facilitate effective treatment plans over time. Interventions are most likely effective when individual and family treatment needs are matched with high-quality services in a seamless and flexible continuum of care.

The continuum of treatment interventions includes:

- Educational interventions.

- Outpatient therapy (6-16 months)

- Intensive outpatient therapy (clinic or home-based).

- Intensive multisystemic treatments, including day treatment, residential treatment, and intensive treatment in locked facilities, such as correctional facilities.

Research suggests treatment is more effective when caregivers and teens are concurrently involved and practice new skills. Depending on the individual and family needs, community-based treatment interventions can vary in intensity. Most teens who have few risk factors associated with reoffending and solid protective factors may only require weekly outpatient treatment sessions.

How can I tailor the intervention to address multiple risk factors?

- Youth and families with more risk factors and needs may benefit from a greater intensity of services as well as home-based or multisystemic services.

- Home-based interventions are appropriate for youth with significant needs across multiple domains, especially ongoing problematic behaviors in their home and school environments.

- The programs often address parenting strategies and youth problem behaviors. Sometimes, they include additional community support and coordination with other providers and settings, such as schools.

- Multisystemic Therapy (MST) for Problematic Sexual Behaviors is an effective intervention method with strong empirical support.

What if families and individual family members have multiple needs?

Multidisciplinary teams or intensive case management services, such as High-Fidelity Wraparound, can help address multiple needs. Case managers and team facilitators must be knowledgeable about youth with problematic sexual behavior, their risks, and their needs.

Find information about evidence-based treatments through the California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse (https://www.cebc4cw.org/) and OJJDP’s Evidence Based Program directory (https://ojjdp.ojp.gov/evidence-based-programs). Below are some examples:

- Locate sites trained in Multisystemic Therapy for Youth with Problematic Sexual Behaviors (MST-PSB) operating under a valid program license from MST Associates (https://www.mstpsb.com/).

- Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavior Therapy (tfcbt.org) is designed for youth whose problematic sexual behavior is driven by trauma experiences.

- Functional Family Therapy (https://www.fftllc.com/) is one of many treatments found to be effective treatment when disruptive behaviors are of primary concern. Modules to address problematic sexual behavior can be integrated.

- OU Problematic Sexual Behavior - Cognitive Behavior Treatment for adolescents. To learn more and find providers (https://connect.ncsby.org/psbcbt/home.)

- Safer Society Foundation (https://safersocietypress.org/treatment-referrals/) maintains a database of clinicians from around North America who work with sexual abusers, children with sexual behavior problems, and survivors of abuse.

- The Association for the Prevention and Treatment of Sexual Abuse (ATSA) (https://www.atsa.com/referral) referral database promotes sound research, effective evidence-based practice, informed public policy, and collaborative community strategies that lead to the effective assessment, treatment, and management of individuals who have sexually abused or are at risk to abuse.

- Search for a local Children's Advocacy Center located near you through the National Children's Alliance (https://www.nationalchildrensalliance.org/cac-coverage-maps/). Local Child Advocacy Centers may provide services directly or guide caregivers to treatment options in their communities.

How can foster care placements help teens with problematic sexual behavior?

For teens who are unable to remain at home, foster care placements offer alternative community-based placements.

- For teens unable to remain at home, foster care or kinship care could be considered as community-based placements.

- Therapeutic foster care or foster homes with services may be good alternatives to avoid exposing youth to negative peer influence in residential care – especially if the youth are not demonstrating a pattern of delinquent behavior.

When should I consider in-patient or residential treatment?

Teens with the highest level of risks and needs may require residential, hospital, or correctional placements with appropriate treatment programs.

Research suggests that while youth in some residential programs demonstrate positive gains, these gains require transitional support in the community with the caregivers for sustained positive impact. Effectiveness of residential treatment may be enhanced by using intensive, evidence-based interventions, as well as involving the family, developing pro-social skills, and transitioning to stable aftercare settings. Ongoing support must follow discharge.

Juvenile corrections programs should incorporate evidence-based interventions, too.

How can I involve caregivers in the treatment process?

Teens are beginning to separate from their parents and caregivers, but those adults remain important facets in their lives. Involving parents will help yield positive outcomes. Our Caregiver Partnership Board has developed a Caregiver Survival Guide and tip sheet on what to look for in treatment. Further, our Youth Partnership Board developed a tip sheet for caregivers sharing how important they are to teens success in treatment. These can help the caregiver feel informed and empowered to help their child.

Topics often addressed in treatment with the caregivers include:

- Effective parenting strategies that promote positive behaviors and prevent misbehaviors.

- Information about sexual development and guidelines for distinguishing more common sexual behaviors from those that are problematic or illegal.

- Vulnerability and protective factors related to sexual behaviors of youth.

- Developmentally appropriate sex education.

- How to promote open communication about sexual knowledge and behavior.

- How to help their teens understand relevant laws and legal consequences for illegal sexual behavior.

- How to address relationship-building skills and ensure consenting relationships.

- Abuse prevention skills, with emphasis on how they can protect all their children.

For additional information about adolescents with illegal sexual behavior, see the guidelines from the Association for the Treatment and Prevention of Sexual Abuse

y developed. Peer relationships are of utmost importance and yet are fraught with uncertainty. All of this is fueled by easy access to technology and sexual content. Although research indicates that youth want access to accurate information on relationships, sex education, consent, and the rules and laws that guide these decisions, few receive quality content. Further, addressing problematic sexual behavior in teenagers is more complex because the behavior may also be illegal, depending on the laws in the jurisdiction. Background information about adolescents' sexual behavior can be

y developed. Peer relationships are of utmost importance and yet are fraught with uncertainty. All of this is fueled by easy access to technology and sexual content. Although research indicates that youth want access to accurate information on relationships, sex education, consent, and the rules and laws that guide these decisions, few receive quality content. Further, addressing problematic sexual behavior in teenagers is more complex because the behavior may also be illegal, depending on the laws in the jurisdiction. Background information about adolescents' sexual behavior can be